Location Taken: Powder River Pass, Wyoming

Location Taken: Powder River Pass, Wyoming

Time Taken: June 2010

It’s a nice hill, isn’t it?

Actually, let me rephrase that…

It’s a gneiss hill, isn’t it?

I love it when the road signs actually talk about the geology of the area around them. It’s really rare, but awesome. This particular pass, in the Bighorn mountains of Wyoming, had a nice string of them telling the rock type and geologic era of the landscape.

I don’t remember what exact era this was (Ordovician, maybe?), but I do remember it was gneiss. Yes, gneiss is pronounced exactly the same as nice. I have made many many bad puns based on that over the years.

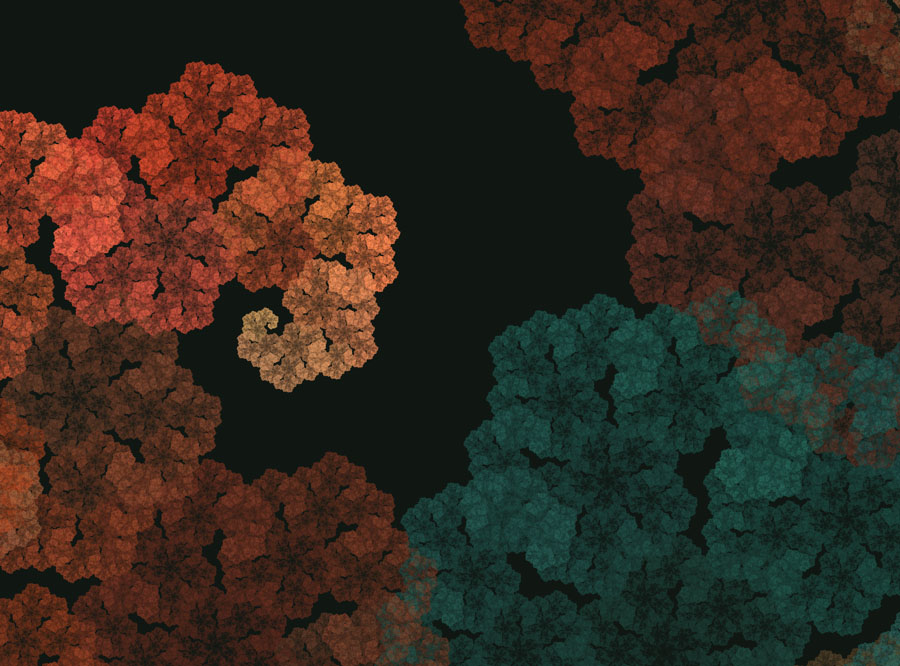

Gneiss is a metamorphic rock, usually formed from granite that got shoved back into the mantle and remelted into a different crystalline structure. Occasionally it’s from a different volcano-produced rock like diorite as well, but granite’s most frequent. It’s a pretty common rock, since granite’s quite common as well, especially in the older rocks when the primary land formation method was volcanism rather than water- or life-based methods.

Yes, life actually has a pretty big impact on the rocks. Heck, another rather common rock, limestone, is made from discarded shells of trillions of sea creatures, piling up over the eons. Banded Iron formations (one of my favorite rock formations with the pretty black and red stripes) only formed during the oxygenation of the planet, caused by life breathing in carbon dioxide and breathing out oxygen.

If that seems backwards to you, congratulations! You remember your basic human biology! Humans and most other animals require oxygen, but the plants and the micro-organisms tend to break apart carbon dioxide and create oxygen. That’s why having a potted plant in your health improves air quality, and why deforestation is such a problem for the environment. We need plants around to keep the cycle going.

…Boy, do I go of on tangents sometimes.

This is another of the cases where knowing more about geology makes the landscape much more interesting. To the standard passerby, it’s just a pile of rocks. But I can tell, just from the rock type, that those rocks formed so long ago that they then sank back into the earth, remelted, were pushed back up in their new form, then pushed further up so that these mantle-kissed rocks are now at the top of a mountain, nearly 10,000 feet above sea level.

Location Taken: Powder River Pass, Wyoming

Location Taken: Powder River Pass, Wyoming